Launching on January 1st 2023: The HSP Revolution online community to support your journey of empowerment as a Highly Sensitive Person (HSP).

In 1964, American psychiatrist Eric Berne published The Games People Play. The five-million-copy bestseller was the fruit of Berne’s years of work to develop a system to help people better understand their everyday interactions, which he called Transactional Analysis.

Berne had found that we often relate to others through habitual, unconscious patterns that resemble games — with unspoken rules. Transactional Analysis aimed to help people enjoy clearer communication, and healthier relationships, by showing how these games typically play out.

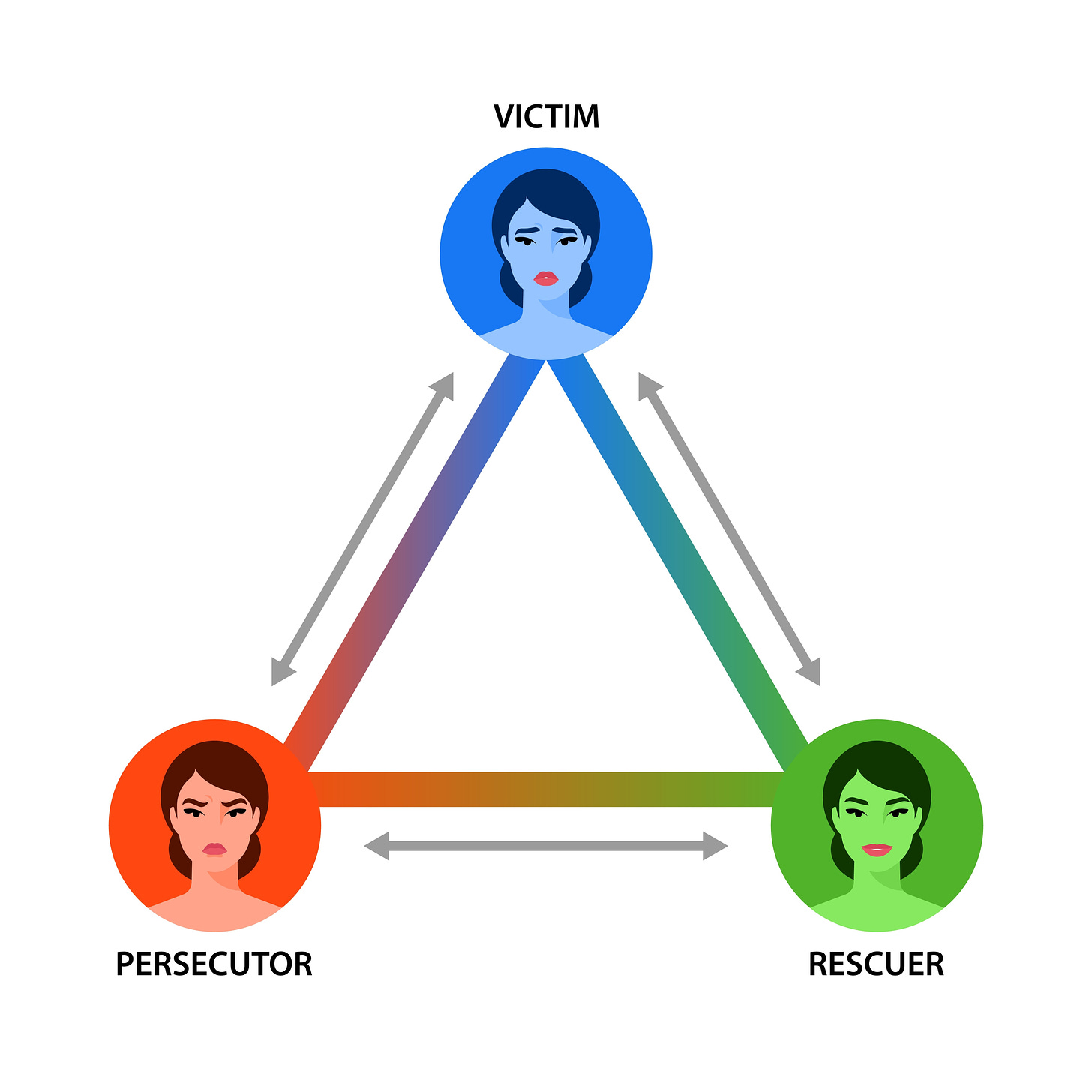

In 1969, Stephen Karpman, a student of Berne’s, built on his mentor’s work to develop a concept called The Drama Triangle, in which people can fall into one of three roles:

Victim: Feels powerless and often gives up on what they want. Believing the world to be against them, they disengage, complain, and feel angry, resentful and envious of others. Difficulties making decisions, solving problems or enjoying life. Looking for a rescuer to solve their problems. Says things like:

“I’m not good enough.”

“This always happens to me.”

“Poor me.”

Persecutor: Blames, criticizes and acts superior to the victim. Certain they know best, they’re poor listeners who ignore what others think. They use criticism to shame the victim into apologising. Persecutors are always former victims. Says things like:

“That person will get what’s coming to them.”

“I must win at all costs.”

“Who’s to blame for this?”

Rescuer: Well-meaning and sincere, the rescuer wants to repair the relationship between the victim and persecutor, but they are often motivated by low self-worth and a desire to avoid looking at their own issues. While a rescuer thinks they are being helpful, they’re actually contributing to the drama by adding more energy to the dance, and often feel underappreciated. Says things like:

“Let me help you”

“You need me.”

“I help so many people but nobody’s there for me.”

I can still remember how fascinated by these roles I was when I first learned about the Drama Triangle during my clinical psychology training. Once you start to see the triangle, you see it everywhere — including in films, literature and fairy tales. You only have to think of Cinderella to envisage an archetypal victim (Cinders), a persecutor (wicked stepsister), and a rescuer (Fairy Godmother). Years later, I’ve seen the victim-perpetrator-rescuer dynamic play out so many times that I believe a basic understanding of it can be very beneficial, particularly for Highly Sensitive People (HSPs).

A certain amount of conflict is normal and healthy in any relationship. But perhaps you’ve noticed that you tend to fall into the same repeating patterns in arguments with your partner, family, children, co-workers or boss.

It can be incredibly draining and frustrating to find yourself trapped in these kinds of cycles — particularly if you’re an HSP who processes emotions deeply, and can easily find yourself feeling drained and overwhelmed by endless tensions with others.

So let’s take a look at how the Drama Triangle can help us notice when we are either giving our power away, or taking power from others — and ultimately free ourselves.

Taking turns

The crucial thing to bear in mind about the Drama Triangle is that once you’ve assumed one of the roles, you’ll end up cycling through the other two as well.

Let’s take an example: Say your friend has had an argument with their partner, and feels so upset that they call you to vent. You might make some innocent suggestions about how she could communicate her needs more directly — and perhaps recommend some podcasts or books you’ve found helpful. By taking responsibility for your friend’s problems and trying to fix them for her, you’ve assumed a classic rescuer position — reinforcing your friend’s role as victim, and her partner’s role as persecutor.

As rescuer, you find yourself doing more and more of your friend’s thinking for her, and going out of your way to make suggestions. But as time goes by, you realise that she isn’t listening, or making any changes in her life — even though she’s always calling or texting you to offload. Before long, you’re annoyed that the friend you’re trying to help isn’t helping herself, and certainly doesn’t appear to be grateful for all the time and energy you’ve invested in her problems.

Gradually, the roles are starting to shift.

Let’s say your frustration prompts you to to blame your friend for getting herself into the situation with her partner — and even get angry with her for not being more appreciative of your concern. Bingo: Now you’ve assumed the role of persecutor. As your friend starts to get reactive, you start to feel hurt and downtrodden — ruminating about why so many of your friendships have ended this way. Hey Presto: Now you are the victim.

The roles we play

In my experience, I’ve noticed that HSPs mostly resonate with either the victim or rescuer role — though the identities we assume will tend to reflect the types of relationships modelled by our parents and caregivers during childhood.

For example, as a child we may have observed our parents arguing, where mum fell into the vulnerable and helpless victim role, dad was the more forceful and controlling persecutor and we — naturally wanting the fighting to stop — played rescuer.

Or perhaps you wanted to be liked at school, and you found you were naturally good at listening, so you became a friendly ear for others and received validation for putting others’ needs first, which cast you as a rescuer.

Since HSPs are so affected by the environment around us, we can easily feel drained by other peoples’ emotions and energies. If we tend to think of our sensitivity more as a vulnerability than an asset, then we might be more susceptible to playing victim.

Although none of us like to think of ourselves as persecutors, it’s inevitable that we will have occupied this position if we’ve ever identified as rescuer or victim. Remember, the persecutor role can be subtle: If you’ve ever been the least bit controlling, blaming or judgmental, or found yourself lashing out, or acting passive-aggressively, it’s likely that others may have experienced you as the persecutor.

Classic rescuer traits

I’ll own that I used to be a rescuer — a common pattern for HSPs, particularly those of us in the caring professions.

Looking back, I can see why being the rescuer came naturally to me. As a teenager, I discovered that helping other people not only meant I gained validation as a good listener, I was able to avoid my own anxieties, which became harder to deny as they intensified in my twenties.

I’ll always remember arriving for my first day of clinical psychology training at Salomons in the Kent countryside, when the instructors asked the group why we wanted to be therapists. We all shared about how we wanted to help other people, but they made one thing very clear: We first had to look at ourselves, and understand our true motivations. We would have to examine whether our drive to help was coming from a place of low self-worth, a need for validation, or because we wanted to avoid our own uncomfortable feelings — or our need to be perceived as a “good” and “kind” person — all classic rescuer traits. Our goal would be to approach our work from a more integrated, self-aware place — where we made sure to take care of our needs first, so we would be able to provide effective help to others.

Finding a way out

In his fascinating and succinct book The Power of TED (The Empowerment Dynamic), David Emerald shows how we can transform the disempowered roles of the drama triangle into more empowered alternatives:

Victims become Creators: The creator stance is the opposite of victimhood: It’s about tapping into your passion, developing a vision, and pursuing a desired outcome. The key is focus on things in life that hold meaning and purpose, and take gradual steps toward the outcomes that you’re trying to achieve.

“A creator is vision focused and passion motivated,” Emerald writes. “To really live into your Creator self, you’ll have to do the inner work necessary to find your own sense of purpose and passion — whatever touches your heart and holds meaning for you.”

Persecutors become Challengers: The challenger helps you to see life’s lessons as opportunities for learning, growth and development. The challenger holds the creator accountable, and is firm but fair. They support the creator to clarify your needs, learn new skills, make difficult decisions and pursue goals.

Rescuers become Coaches: The coach sees you as capable of making your own choices, solving problems and acknowledges your resourcefulness and creativity — using compassionate questioning to help you to develop a vision, and an action plan for achieving it. The coach asks questions like:

“What would you like to see happen?”

“What do you think you can do to change this?”

“What do you want to experience in your life?”

As with any intention we may set to change a habitual pattern, cultivating greater self-awareness is the key.

Emerald suggests setting side a few minutes each day to notice the choices you’re making, sit quietly in gratitude, and invite guidance.

The invitation is to think like a problem-solver: Ask yourself what small steps you can take now to get closer to what you want?

And that’s how you can walk away from the drama, and follow a more satisfying, purposeful and passionate path.

Here’s wishing everyone a creative weekend!

See you next week,

Ha, it's blowing my mind how many things have popped up this week relating to my current self-healing trajectory; shadow work, inner child, core beliefs, wanting to be seen as a "good man", overresponsibility, slipping into rescuer mode all the time with victim and persecutor roles also popping up... Thanks for this, it's like something new relating to these interconnected aspects of my healing is appearing every day! Big love x